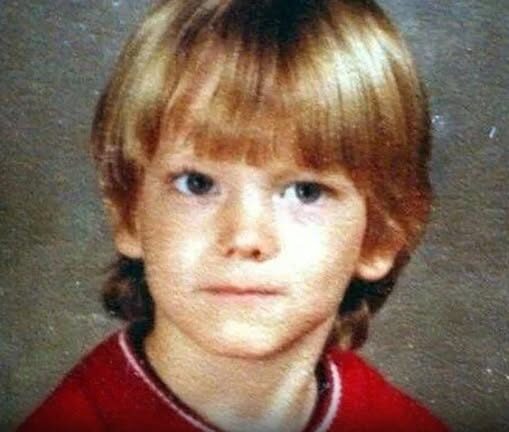

At just nine years old, that cruelty nearly killed him. During a playground game of “King of the Hill,” a bully struck Marshall in the head with a hard object hidden inside a snowball. The impact caused a severe concussion and a brain hemorrhage. He slipped into a coma that lasted five days. The incident permanently altered his sense of safety, teaching him early that no institution—school, authority, or system—was going to protect him.

Home offered no refuge. Marshall has described his childhood household as chaotic and volatile, filled with emotional neglect and instability. His mother struggled with addiction and emotional consistency, and while she later contested his portrayal—going so far as to sue him for defamation—his perception of abandonment was real and formative. In the absence of reliable parents, Marshall bonded deeply with his uncle Ronnie Polkingharn, who introduced him to hip-hop. Ronnie became a rare source of encouragement and understanding. When Ronnie later died by suicide, Marshall lost one of the only figures who had made him feel seen. The loss locked hip-hop into his identity—not just as music, but as survival.

By his teenage years, Marshall had found his outlet. In Detroit’s underground rap scene—predominantly Black and fiercely protective of its culture—he was an anomaly: a poor white kid from the wrong side of town trying to earn respect through skill alone. He understood immediately that talent wasn’t enough. He had to be exceptional.

Night after night, he battled at open-mic competitions, especially at the legendary Hip-Hop Shop on West 7 Mile Road. His technical precision, rapid delivery, and brutal honesty slowly silenced skepticism. Around this time, he created Slim Shady—a confrontational, dark alter ego that embodied every suppressed rage, insecurity, and intrusive thought he had accumulated since childhood. Slim Shady was not just shock value; it was armor. Through that persona, Marshall could say the things polite society refused to confront.

Everything changed when a demo reached Dr. Dre. Dre’s decision to sign Eminem was a risk that defied industry norms, but the chemistry was undeniable. The Slim Shady LP (1999) detonated across the music world. It blended satire, horror, and autobiography in a way that forced listeners to confront uncomfortable truths about poverty, rage, and neglect. Eminem wasn’t asking for sympathy—he was demanding attention.

As his fame exploded, so did the stakes of his personal life. In 1995, Marshall became a father. The birth of his daughter, Hailie Jade, reshaped his priorities overnight. For the first time, his life was no longer about survival alone—it was about breaking a cycle. His music softened in moments, revealing vulnerability beneath the aggression. Songs like Mockingbird and Hailie’s Song exposed a man desperate to give his child what he never had: stability, protection, and presence.

He would later extend that commitment by raising his niece Alaina and his child Stevie, further rejecting the neglect that defined his own upbringing.

Eminem’s cultural dominance crystallized with the release of 8 Mile in 2002. The semi-autobiographical film captured the desperation of Detroit’s battle-rap scene, culminating in Lose Yourself. The song’s raw urgency resonated far beyond hip-hop, earning the Academy Award for Best Original Song—the first rap track ever to do so.

Yet success did not erase his demons. The mid-2000s saw Eminem battling severe prescription drug addiction, a struggle that nearly cost him his life. His 2010 album Recovery was exactly that—a public confrontation with relapse, accountability, and survival. Rather than hiding his failures, he turned them into testimony.

Today, Eminem stands as one of the most influential artists in music history—over 220 million records sold, inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and studied as a technical master of lyricism. Despite his global stature, he remains rooted in Detroit, fiercely loyal to the city that shaped him through hardship.

His legacy is not simply one of controversy or commercial success. It is a legacy of endurance. Marshall Mathers proved that abandonment does not have to define destiny, that pain can become precision, and that words—when sharpened by truth—can transform suffering into something immortal.

He didn’t just survive the hill he was once beaten on.

He claimed it—and never let go.