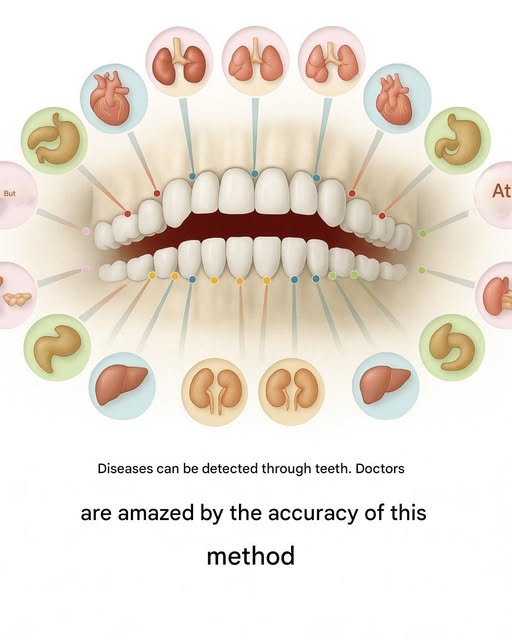

The journey through the dental map begins with the incisors, the sharp front teeth located in both the upper and lower jaws. These prominent teeth are believed to be the primary indicators for the kidneys and the urinary system. If a patient experiences recurring sensitivity or dull aches in the incisors that a dentist cannot explain through traditional x-rays, it may be a sign of a deeper imbalance within the urinary tract. Proponents of this theory suggest that such dental pain could be a precursor to chronic pyelonephritis, a bladder infection, or even issues related to the middle ear, such as otitis media. Because the kidneys are essential for filtering toxins and maintaining fluid balance, discomfort in the front teeth serves as a vital prompt to evaluate one’s renal health and hydration levels.

Moving slightly back, we encounter the canines, the pointed teeth often referred to as “eye teeth.” These are traditionally linked to the liver and the gallbladder—the body’s chemical processing plants and waste management centers. Sensitivity in the canines is often interpreted as a sign of liver congestion or gallbladder stagnation. In some cases, persistent pain in the first upper incisors or canines might be a subtle early warning for conditions like hepatitis or cholecystitis (inflammation of the gallbladder). When the liver is overwhelmed by toxins or emotional stress, the canine teeth act as a pressure valve, alerting the individual to a need for detoxification or dietary changes to support these vital metabolic organs.

Further along the dental arch are the premolars, the fourth and fifth teeth from the center. These are energetically mapped to the lungs and the large intestine (the colon). Pain in the premolars, particularly those in the lower jaw, can be a fascinating indicator of respiratory or digestive distress. Individuals suffering from chronic asthma, bronchitis, or persistent rhinitis may find that their premolars become inexplicably sensitive during flare-ups. Likewise, issues within the colon, such as colitis or chronic constipation, can manifest as discomfort in these specific teeth. This connection highlights the relationship between the body’s intake of oxygen and its ability to eliminate waste, suggesting that a toothache in the premolar region is a call to breathe more deeply and nourish the gut.

The molars, the sixth and seventh teeth, represent some of the most complex systemic links in the dental meridian map. These large, grinding teeth reflect the status of the stomach, pancreas, and spleen, as well as the health of the joints. Pain in the upper molars is frequently associated with digestive disorders such as gastritis, duodenal ulcers, or even systemic conditions like anemia. Conversely, pain in the lower molars may be a herald for inflammatory issues such as arthritis or colitis. In some instances, lower molar discomfort has even been linked to the early stages of arteriosclerosis, indicating a potential hardening of the arteries. Because the stomach and pancreas are central to nutrient absorption and energy production, health issues in the molars often coincide with feelings of fatigue or chronic digestive discomfort, signaling that the body’s “engine” is in need of maintenance.

Finally, we reach the wisdom teeth, or third molars. These often-problematic teeth are uniquely associated with the heart and the small intestine. Because the wisdom teeth are the last to erupt and are positioned at the very back of the jaw, they are also deeply connected to the central nervous system and the body’s overall energetic balance. Pain or impaction in the wisdom teeth is sometimes thought to mirror imbalances in the heart’s rhythm or functionality. Furthermore, since the small intestine is the site of most nutrient absorption, wisdom tooth distress can indicate a lack of assimilation—not just of food, but of life experiences and emotional data. When the nervous system is under extreme duress, the wisdom teeth are often the first to flare up, acting as a final warning that the heart and mind are overextended.

While traditional Western dentistry focuses on the physical structure of the tooth, these alternative perspectives encourage a more holistic approach to well-being. It is important to note that dental pain can also persist in “phantom” form even after a tooth has been extracted, suggesting that the meridian connection remains intact regardless of the physical presence of the tooth. If an organ is struggling, the site where the tooth once stood may still experience sensation, further proving that the body’s energy channels are persistent and profound.

Ultimately, viewing dental health through the lens of systemic interconnection encourages individuals to listen more closely to their bodies. A toothache does not have to be merely an inconvenience to be numbed or drilled; it can be a valuable diagnostic whisper from the kidneys, the lungs, or the heart. By cross-referencing oral pain with the dental meridian map, we gain a new perspective on preventative care. This approach does not replace the necessity of professional dental work, but it adds a layer of insight that allows us to treat the person as a whole rather than a collection of separate parts. In this integrated view of health, every tooth is a window into the soul of the body’s internal architecture, providing a roadmap toward deeper healing and long-term vitality. By paying attention to these dental indicators, we can address the root causes of disease long before they manifest as chronic illness, ensuring that both our smiles and our internal organs remain in harmonious health.