The legend of Lieutenant Columbo rests on a series of striking contradictions: a worn trench coat covering a razor-sharp intellect, a beat-up Peugeot masking a man of hidden sophistication, and a casual “just one more thing” that became a deadly psychological tactic. To truly understand the man beneath the rumpled exterior, one must look beyond the cigar smoke and the half-squint. Peter Falk didn’t simply portray Columbo—he infused the character with pieces of his own insecurities, turning personal vulnerability into a tool of narrative power. The shuffling gait, hesitant voice, and seemingly meandering questions were more than stylistic quirks; they were calculated strategies designed to unsettle the overconfident and expose their flaws.

Falk grasped a key truth about authority: those in power often overestimate their own brilliance. By presenting Columbo as clumsy, distracted, and socially unassuming, he coaxed wealthy antagonists into underestimating him. The audience saw a patient, morally grounded hero, but Falk was channeling his own internal battles: lingering doubts, suppressed anger, and an ongoing hunger for recognition he rarely admitted to. The character became a mirror, projecting external simplicity while concealing a complex internal life.

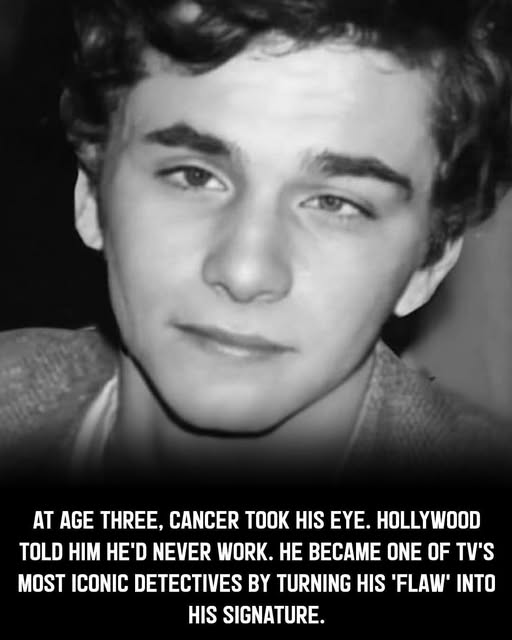

Central to Falk’s persona was his glass eye, lost in early childhood to retinoblastoma. That physical loss became both a defining characteristic and a metaphor for his sense of otherness. On-screen, it contributed to Columbo’s famous squint, signaling a mind always several steps ahead. Off-screen, it symbolized a lifelong duality: one eye on the world, the other turned inward toward a private, sometimes bleak landscape. This perspective shaped Falk’s interactions, leaving him perpetually slightly detached, an observer of life rather than a full participant.

Fame offered paradoxical rewards. To viewers, Falk was the underdog who brought justice to the powerful. Behind the applause, however, he contended with persistent restlessness. Perfectionism guided his work with directors like John Cassavetes, yet complicated his personal relationships. The acclaim could not silence the inner critic or soothe the complexities of his private life.

When the cameras stopped, Falk often sought refuge in drink to manage the relentless mental pressure. His personal life was complicated—affairs and volatile moods colored his domestic reality, which was far less orderly than the fictional world of Columbo and his unseen, steadfast spouse. Falk thrived in creative tension, leaving a trail of exhaustion among friends and family who bore witness to both his brilliance and his intensity.

Columbo’s appeal lay in the certainty of justice: every story followed a predictable path to confession, offering a comforting illusion of moral order. Falk’s life, by contrast, rarely offered such clarity. In his later years, Alzheimer’s disease stripped away the very memory and acuity that had defined his genius, an ironic final chapter for a man celebrated for his perceptiveness and keen observation.

Even as his health declined, Columbo’s image remained firmly in the public consciousness. Falk and the lieutenant became inseparable in the minds of fans; the actor’s private struggles were largely invisible behind the icon he created. The “shambling walk” mirrored Falk’s unconventional path in Hollywood—a man who never fit the standard mold of a leading man but leveraged his authenticity to transform the detective genre. He proved that intellectual sharpness and human vulnerability could redefine heroism.

Falk’s career is a study in the cost of creative excellence. To forge a character as enduring as Columbo, he transformed insecurities into strengths, physical limitations into defining traits, and internal struggles into narrative fuel. His work rendered justice inevitable on-screen, while his own life remained marked by complexity and hardship.

Ultimately, Peter Falk existed between extremes. He was the moral hero contending with personal demons, the acute observer who felt perpetually misunderstood, and the celebrated actor who remained, at heart, the determined boy from Ossining, New York, striving to prove his worth. The glass eye symbolized a vision simultaneously cynical and hopeful—a reminder that while order may be restored in a sixty-minute episode, human hearts remain enigmas even the great Lieutenant Columbo could not solve. Falk’s legacy endures as a portrait of genius forged from vulnerability, a testament to the power of turning one’s fractures into art.