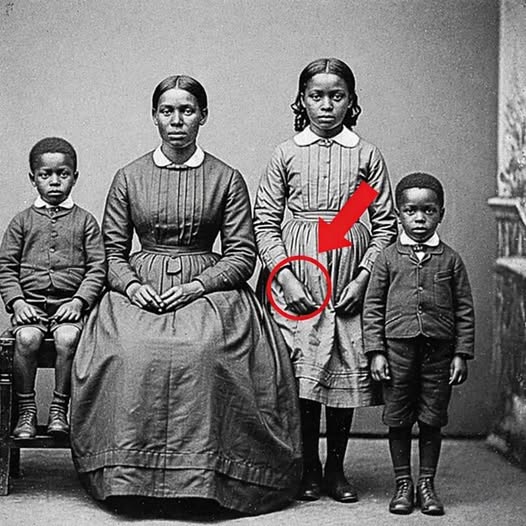

Standing near the center of the frame was a young girl, her posture upright and her gaze steady. But on her small, exposed wrist, there were faint, unmistakable markings. They were perfectly circular, etched into the skin with a geometric precision that ruled out the possibility of fabric creases or accidental bruising. They were too uniform to be the result of a photographic glitch or the natural degradation of the chemicals on the plate. These were indentations in human flesh—marks of restraint so deep and so frequent that they had left a permanent physical record on the child’s body. Sarah realized in a moment of chilling clarity that she was looking at the scars left by iron shackles.

This discovery peeled back the veneer of the portrait’s domestic tranquility. The photograph was no longer just a family record; it was a testament to a life lived in the shadow of bondage, captured at the exact moment that life was attempting to redefine itself in the light of freedom. Driven by a newfound sense of urgency, Sarah began to hunt for the origins of the image. Along the bottom edge of the print, she found a nearly invisible studio stamp. Though faded by over a century of light and dust, two words remained legible: “Moon” and “Free.”

That fragment of information led Sarah to the history of Josiah Henderson, a pioneering African American photographer of the Reconstruction era. Henderson was known among the Black communities of Virginia as a man who documented “The Great Transition.” His studio was a sanctuary where formerly enslaved families went to claim their personhood. In an age where they had been treated as property—nameless, faceless, and disposable—Henderson provided them with something revolutionary: proof of their existence. By sitting for a portrait, these families were asserting that they were no longer objects to be owned, but citizens to be seen.

With the photographer identified, the genealogical threads began to knit together. Through a painstaking search of Richmond census records, church ledgers, and property deeds from the 1870s, the family finally stepped out of the fog of anonymity. Their surname was Washington. The father, James, had established himself as a laborer in the city, working grueling hours to provide for his wife, Mary, and their five children. The young girl with the marked wrists was named Ruth.

The historical context of Ruth’s scars painted a grim picture of the era that preceded the photograph. During the years of slavery, children were often subjected to mechanical restraints to prevent them from wandering or attempting to flee from the plantations where they were forced to work. These “quiet” cruelties were a means of control, designed to break the spirit before it had a chance to grow. Ruth had entered the world as a commodity, her body subjected to the literal weight of iron. Yet, here she was in 1872, standing in a photographer’s studio, wearing a clean dress and surrounded by the family that had survived the fire of abolition alongside her.

The photograph captures a profound dichotomy. On one hand, it shows the success of the Washington family’s transition. James and Mary had achieved what was once a legal impossibility: a stable, autonomous household. Records showed that their children were enrolled in school, learning to read and write—acts that had been punishable by death just a decade prior. On the other hand, the photograph refused to let the past go. Ruth’s wrist was a bridge between two worlds: the world of the shackle and the world of the pen.

Decades after the photograph was taken, a descendant of the Washington family uncovered a handwritten note in the margins of a family Bible that had been passed down through generations. The note, attributed to one of James’s sons, read: “My father wanted us all in the picture. He said the image would outlast our voices.” James Washington understood that while their physical bodies would eventually fail and their personal stories might be forgotten by the wider world, the photograph would remain as an objective witness to their dignity. He knew that for a people who had been systematically erased from history, the visual record was a form of resistance.

Today, the portrait of the Washington family is no longer tucked away in a dark drawer or a digital folder. It has become a centerpiece of an exhibition dedicated to the resilience of Black families during the Reconstruction. When visitors look at the image, they are often drawn first to the father’s protective hand on his son’s shoulder or the mother’s proud, weary eyes. But inevitably, their gaze settles on Ruth’s wrist.

That small, circular mark speaks with a volume that no orator could match. It does not shout with the anger of a protest, nor does it weep with the self-pity of a victim. It simply exists. It is a quiet, permanent accusation against the system that tried to own her, and a triumphant declaration of the system that failed to break her. In the stillness of the archive, the Washington family finally has their say. The photograph is no longer a silent relic of 1872; it is a living voice, reminding every observer that history is not found in the grand declarations of kings, but in the smallest details of a child’s hand. Through Sarah Mitchell’s lens and Josiah Henderson’s shutter, Ruth Washington continues to stand, marked but free, her story finally heard by a world that once tried to ensure she would never have one.